Apr 30, 2020

Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a Potted Biography of Nagoya’s Pauper Prince

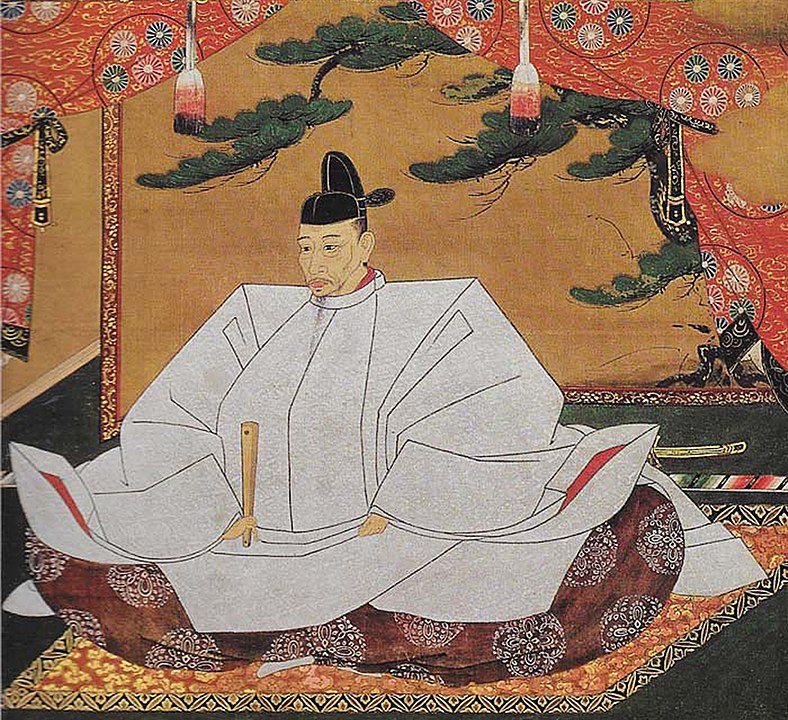

In a world of strict social code, stringent class, and unbreakable caste systems, the samurai era was not a time when upward social mobility was to be dreamed of, let alone expected. However, despite it all, one man rose from peasanthood to become only the second leader of a unified Japan. That man was Toyotomi Hideyoshi

From peasant life to adventure

Though little is known for sure of Hideyoshi’s early life, the accepted story has it that he was born in 1537 in what is now Nagoya’s Nakamura Ward, and his father, a peasant foot soldier, died when he was just seven years of age. It is believed that he was sent to live in a monastery, but being an adventurous child, he ran away to join the service of a samurai family.

Oda Nobunaga

Eventually, by way of fortune, misadventure, and perhaps a little theft, he found himself in the charge of the Oda clan. He became the sandal bearer of the family’s head: the fearsome daimyo [warlord], Oda Nobunaga. Legend had it that Hideyoshi endeared himself to Nobunaga by way of his skill with tea. After a particularly strenuous day, the young man served his master three cups, the first a weak, cool bowl that slaked the daimyo’s thirst. The second was warmer and thicker, which settled the nerves, and the third was thick and rich, just how he liked it. Recognizing Hideyoshi’s attention to detail in his master’s requirements, Nobunaga kept the young man close, as the Oda clan fought their way to become the most powerful in Japan.

The death of a mentor

Hideyoshi’s star continued to rise, and despite his diminutive stature and fiercely ugly features – one contemporary description of him is as a “bald rat” – the ambitious man grew to become one of Nobunaga’s most trusted lieutenants, leading a number of battles and being appointed the position of daimyo to some districts.

However, another of Nobunaga’s generals proved not so loyal, and in 1582, Akechi Mitsuhide turned on his leader, forcing Nobunaga to commit ritual suicide at Honnō-Ji Temple in Kyoto. Incensed, Hideyoshi made alliances with the Mori clan and avenged his master’s death, defeating Mitsuhide at the Battle of Yamazaki, in doing so, marking himself out as one of the leading daimyos.

He had always believed himself to be a man of greatness. He once boasted in a letter demanding the submission of another Asian power that his mother had dreamt around the time of his conception that diviners gathered and stated ‘When he reaches the prime of life, his virtue will illuminate the four seas, his authority will emanate to the myriad peoples’. Now that greatness was coming to fruition.

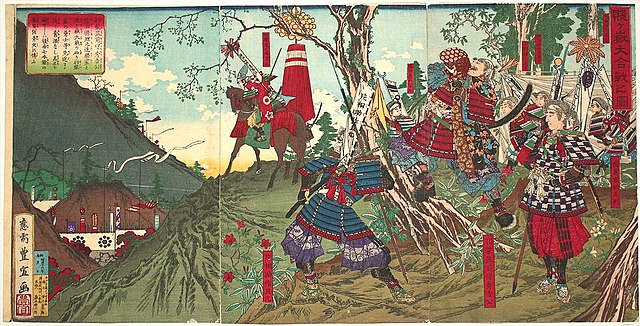

Battle of Shizugatake

Utilizing this newfound authority, Hideyoshi assembled the heads of the Oda clan at Kiyosu Castle where an heir would be decided. Of course, fraternal disagreements splintered the family, and Hideyoshi sided with Nobunaga’s grandson, Samboshi, opposing himself against the General Shibata Katsuie. The pair met in the Battle of Shizugatake, said to be “one of the decisive battles in Japanese history”, and Hideyoshi emerged victorious. Then, following skirmishes at Nagakute and Komaki, Hideyoshi found himself the head of the Nobunaga clan, and in doing so, became the most powerful leader in Japan

To the winner go the spoils

In 1583, Hideyoshi began the construction of an immense fortress at Osaka Castle, and two years later was proclaimed regent (kampaku) by the Imperial court in Kyoto, taking the historical family name of Toyotomi the following year. Having eventually unified most of the country by way of either brutal repression or threats, to prevent any peasant uprisings (or more likely, other daimyos using their peasants as an armed force against him) he decreed the lower classes were forbidden from bearing arms and confiscated vast quantities of swords. It is interesting to see that Hideyoshi, who had risen from lowly beginnings, solidified the class system, effectively pulling the ladder up behind him.

Conquest and Empire

Despite his years and fading health, this man who had pulled himself up and out of the gutter by his sandal straps did not feel his wild ambition diminish. Having defeated his enemies at home, he sought more lands to conquer. Though he had relinquished his title of kampaku to his nephew and heir, Hidetsugu, he retained his power through his new title of taikō, or retired regent. (Throughout much of Japanese history, we find examples of official heads of state as little more than figureheads, with the retired leaders assuming actual authority.)

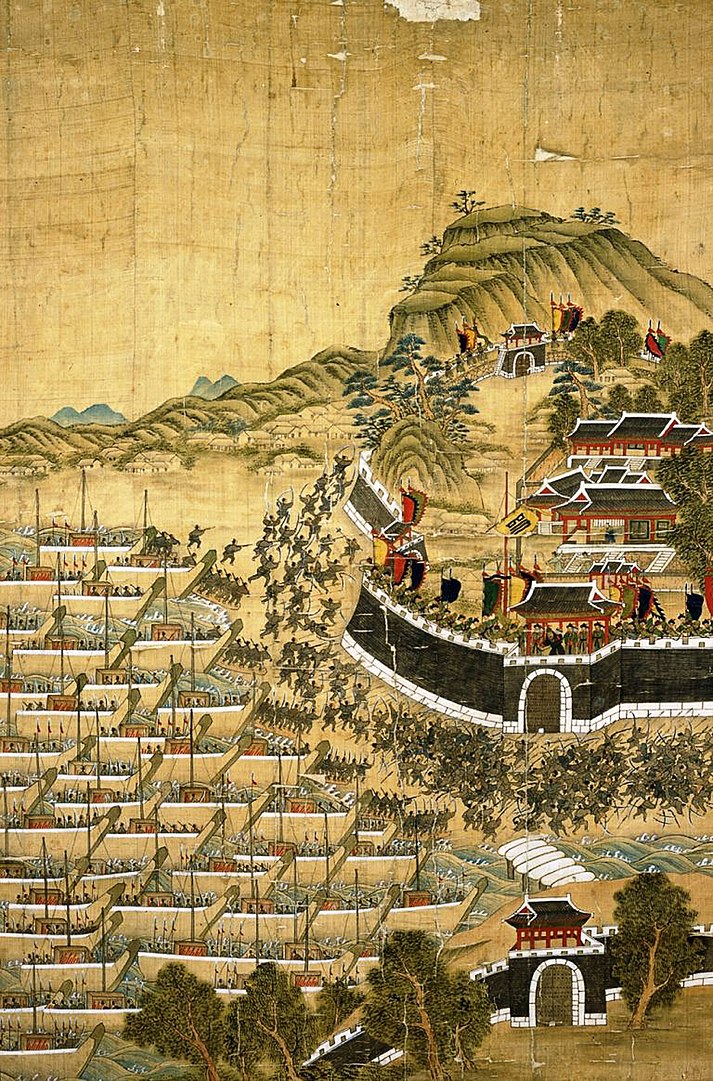

The Japanese land at Busan

Hideyoshi revisited his mentor Nobunaga’s dream to expand the Japanese empire into China, and in 1592 launched an attack upon the Joseon dynasty of Korea, allies of the Chinese Ming dynasty. The Koreans being no match for the brutal and battle-hardened Japanese, Busan fell immediately and Seoul not long after. However, with the Koreans resorting to guerrilla tactics, they refused to be cowed. Though the Japanese won battle after battle, they remained unable to land a decisive blow or attain their objectives, a situation that proved ruinous when the Chinese eventually struck back. Also, the Korean Navy – far superior to its army – destroyed its Japanese opponents, and with supply lines cut, the Japanese fell back. A second invasion in 1597 provided some success as the Japanese fought with previously unheralded brutality and cruelty, and “many thousands of Koreans were killed or mutilated. No distinction was made among combatants and noncombatants” Even so, this invasion too failed, and an expensive and unpopular excursion into empire came to an end.

Hideyoshi had dreamed of Chinese conquest as his lasting legacy, however as it failed, so too did his health, and he passed away in September 1598.

Death and legacy

Hideyoshi’s death opened up a power vacuum in unified Japan. In 1593, his second wife had given birth to a son, Hideyori, and to ensure that there would be no issues surrounding succession, he had his nephew and heir Hidetsugu commit ritual suicide. However, as Hideyori was only five years old at the time of his father’s death, a council of five elders was put in place to rule until he came of age. These powerful daimyos were, quite unsurprisingly, neither able to reconcile their differences nor keep their ambitions in check, and their fractious relationships lead once more to civil war.

And so, the legacy Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the man who had risen from the peasant lands of Nagoya to become the supreme leader of Japan, ended in tatters. His international excursions not only resulted in defeat but also depleted both the wealth and standing of the Toyotomi family. Furthermore, when the armies of his faithful retainer Ishida Mitsunari were defeated at the Battle of Sekigahara, it was another son of Aichi, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who became Shogun, and the Toyotomi heir Hideyori committed suicide during the 1615 siege of Osaka Castle at the age of 21.

But that is not to say that Hideyoshi is one of history’s forgotten men. He is still revered today as one of the three Great Unifiers of Japan. Furthermore, as a great patron of the arts, he is also remembered as a leader in the advancement of the tea ceremony. Not that this would have been much of a comfort for a man possessed of such ambition, and brutality, as Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Image By Kanō Mitsunobu via wikicommons [Public Domain]

Image: via wikicommons [Public Domain]

Image By Utagawa Toyonobu via wikicommons [Public Domain]

Image: via wikicommons [Public Domain]

About the author