Jan 27, 2022

Setsubun: The Bean-Throwing Festival

In the old Japanese calendar, spring arrived at the beginning of February. Setsubun, which means “seasonal division,” commemorates the end of winter and the start of the weather turning mild. It is held before the first day of spring, or Risshun, and falls between February 2 and 4. Although Setsubun is not a national holiday, it is an important day, and it comes with some fun traditions, including the throwing of beans.

Rituals and Traditions of Setsubun

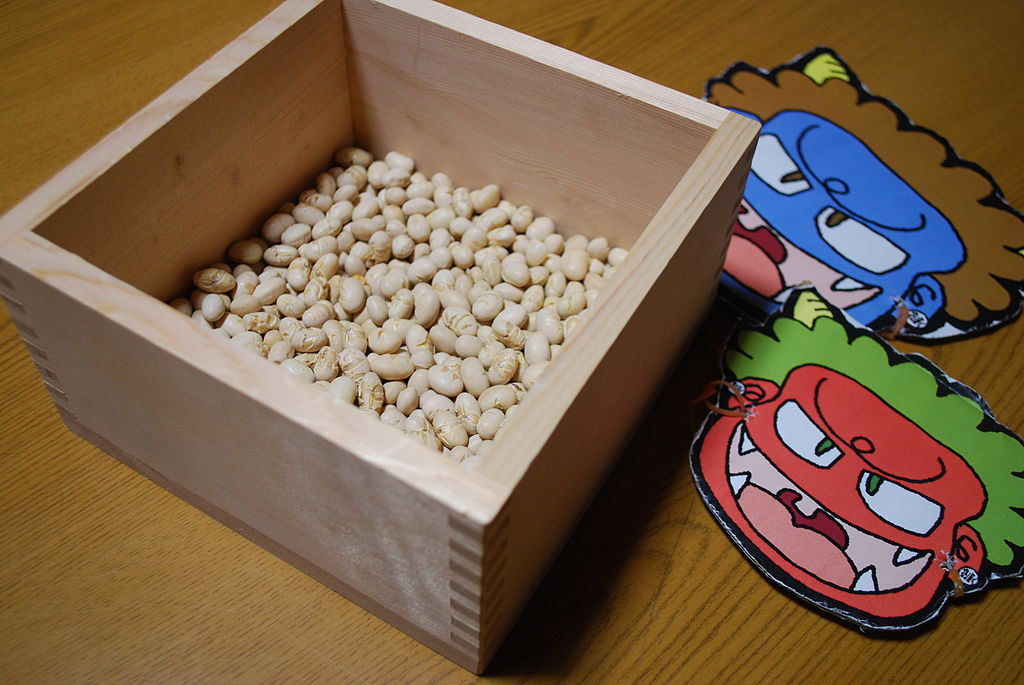

Throwing beans at Setsubun is called mamemaki, which means “bean scattering.” The beans are roasted soybeans called “fortune beans” that, like rice, are supposed to have sacred qualities. Custom dictates that you should throw beans out the front door and then slam the door shut.

Typically, just one household member throws the beans, particularly a man whose Chinese zodiac animal is the same as the current year’s. Alternatively, a family member (often the father) can dress as a demon, and the children can throw beans at him. This option is particularly popular in households with young children. While throwing beans, people shout, “Oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi!” which means “Demons out, good luck in!”

At the end of the bean throwing, you should pick up and eat the same number of beans as your age. You take one extra bean to represent the coming year in some regions. This ritual brings you good health. A second tradition that used to be in Osaka and has now spread throughout the country is eating uncut makizushi called eho-maki — meaning “lucky direction roll.” The name comes from the fact that you should eat your roll while facing whatever compass direction is lucky that year as specified by the year’s zodiac symbol. You need to eat the entire roll without talking to ensure you receive good luck.

Eho-maki is typically only eaten during Setsubun, but you can often find it available (for a discount) up to a few days after the festival. Usually, it has ingredients — often including tuna and egg — because seven is a lucky number.

The Origins of Setsubun

The idea of cleansing in the spring involves chasing away evil spirits and ridding the new year of misfortunes from the previous year has existed for centuries. It’s likely that Setsubun specifically comes from tsuina, a variant of Chinese folk religion, which brought the concept to Japan around the 8th century.

The rituals associated with Setsubun have varied over the years. For instance, in the 13th century, people would burn sardine heads and beat drums — the idea was that the burning smell and noise would drive away evil spirits. This tradition has transformed today into decorating entranceways with fish heads along with holly leaves.

To observe the traditions of Setsubun, go to a Shinto shrine or Buddhist temple. Some hold ceremonies where the priest throws the attendees chocolates, money, and other treats as well as beans. In Kyoto, an apprentice geisha often dances, throwing bags of roasted beans. After the ceremony, buy an eho-maki to eat — and make sure you stay silent until you’ve finished the entire roll for good fortune this year.

katorisi, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

About the author